There are several possible reasons why two or more disorders may occur at the same time.

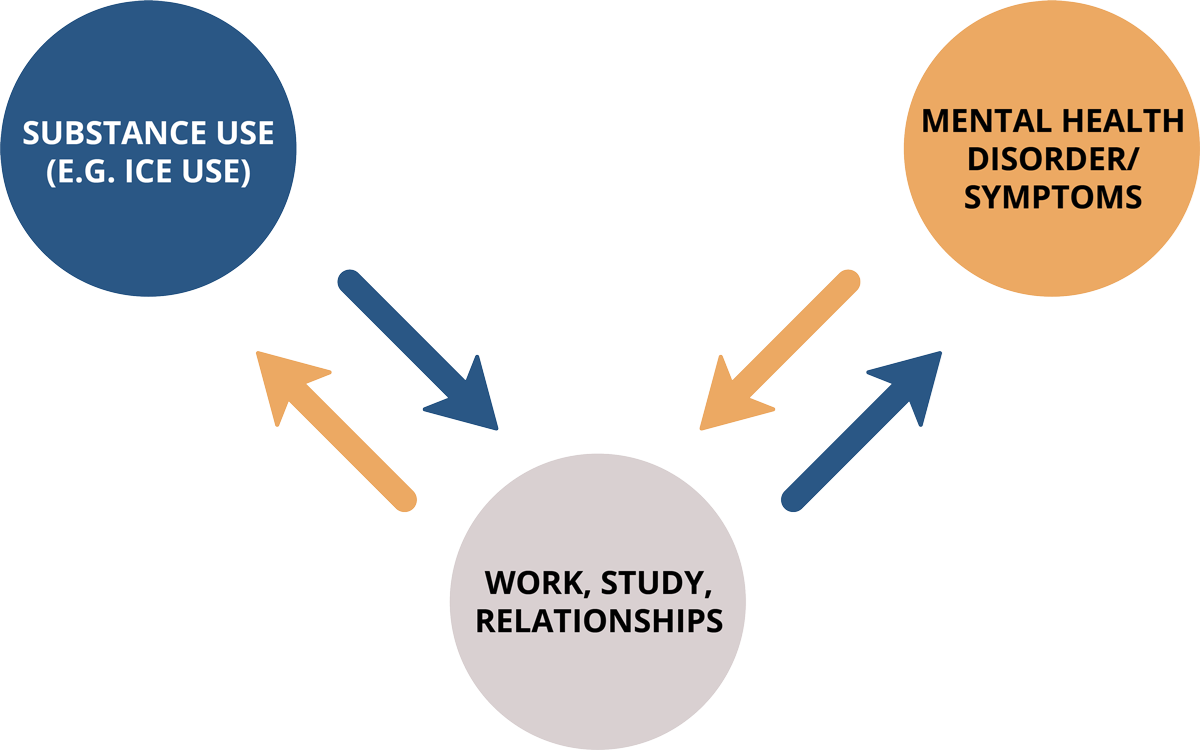

One condition may indirectly cause the other. Poor mental health may cause life difficulties that lead someone to use alcohol and/or other drugs. For example, the experience of mental health problems may limit someone’s ability to study or work. Someone in this position may start using alcohol or drugs to manage the stress of not being able to study or work how they would like to. In the opposite direction, using alcohol and/or other drugs may limit someone’s ability to study or work. The stress of not being able to study or work how they would like to, may then impair their mental health.

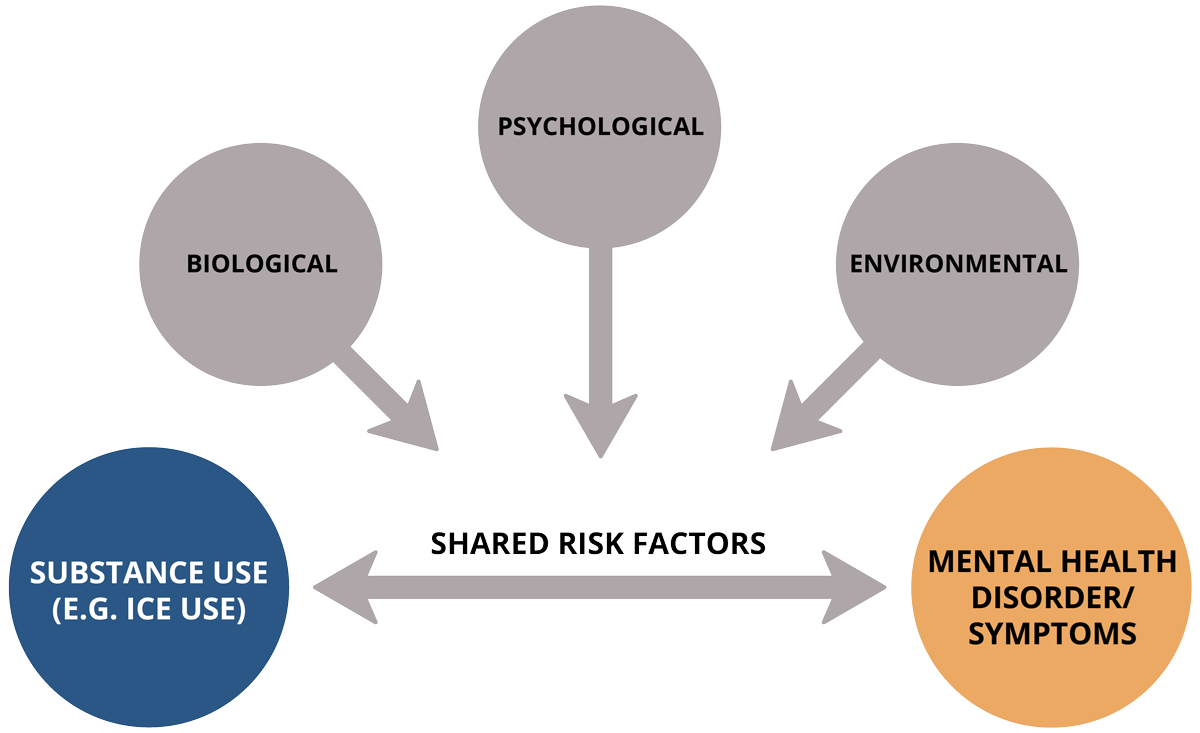

Both conditions may be caused by something else. Sometimes two conditions can be caused by a shared biological, psychological, social or environmental risk factor. A shared risk factor is something about a person or their circumstances that increases their risk of experiencing each of the conditions. For example, both substance use disorders and mental health conditions have been associated with cognitive impairment and lower socioeconomic status.

A lot of research has been conducted to determine which disorder typically develops first out of the different co-occurring substance use and mental health disorders people experience. The evidence so far is not consistent, and researchers have found differences depending on a person’s gender as well as the specific types of mental health disorder/s people are experiencing.

Understanding when different substance use and mental health disorders develop and how they interact with one another can help us to understand how best to prevent them from occurring. But sometimes this is tricky to work this out – it can be a bit like the ‘chicken or the egg’ example when trying to work out if a mental health disorder has come first, or whether a substance use disorder has come first. This can also be tricky because often the symptoms of mental and substance use disorders overlap and emerge at similar points in time during adolescence.

Regardless of which disorder has come first, once these disorders have developed, they most likely maintain and exacerbate one another. This can make it difficult for people to recover if they aren’t able to access treatment for both conditions. For example, someone may use alcohol and/or other drugs to reduce symptoms of yet research shows that repeated use of the substances can lead to increased anxiety for people. Regardless of what order these different disorders develop in, the strategies used to manage them remain the same.